Figure

1

Figure

1Why Interfere? The Relationship between Student Violence and Parental Influence

Mallory Maschhoff

Abstract

The parent-adolescent relationship seems to be an integral part in the development of adolescents including the likelihood of adolescent violence. The current study used data from a sub-sample of the Kentucky Youth Survey. Scales were created to represent �Parental Involvement,� �Parental Communication,� and �Violence.� Then, regression models were used to determine the relationship between each �parental� variable and violence. Results indicated a significant and negative relationship between parental involvement and violence. However, a significant and positive relationship was indicated between parental communication and violence. These findings may be useful for those involved in the upbringing of children and adolescents.

Today�s parents are faced with thousands of choices when it comes to their children. They must decide everything from what to name them, to where the children will attend school, to what acts deserve punishment, and how severe that punishment will be, but one of the most difficult decisions parents must make is how and when to talk to their children about the �big three:� drugs, sex, and alcohol. Normally, �the talk� between parents and their children occurs in the child�s teenage years; however, in today�s society, it is occurring much earlier. Although this is a significant part of the parental procedure, many do not know how to best go about approaching these topics with young people.

Along the same lines, parents also struggle with how involved they should be in their children�s lives. How to find the correct balance of supervision and independence can be a difficult battle for parents. In the same way, parents have to decide how they want their children to see them, for instance either as a friend or as a boss. They must decide when to press an issue and when to let one go; they must decide if as parents they want to question their child or children on where they are and who they are with. They also must decide how much trust and leniency to give their children.

However, what also needs to be taken into consideration is the effect these parental choices have on the decisions of the children. Perhaps there is a relationship between certain actions a teenager will participate in and the level of involvement of his or her parents or perhaps the lack of having �the talk� with a teenager is also related to certain actions a teenager will participate in. In this study, the actions that will be focused on in relation to the level of parental involvement and �the talk� will be violent actions of students. The current study has two aims; the first is to show a negative correlation between parental influence in the lives of high school students and violent behavior exhibited by high school students. The second aim of the current study is to provide support for the hypothesis that a student who has talked to his or her parents about drugs, alcohol, and sex will show fewer signs of violent behavior than a student who has not talked to his or her parents about drugs, alcohol, and sex.

Review of Literature

Control Theory. Unlike other criminologists Travis Hirschi did not focus on why people engage in deviant acts but rather why they do not engage in deviant acts. Hirschi seems to focus on juvenile delinquency, and it appears as though his theoretical control model focuses on the individual rather than on society as a whole. In his 1969 Causes of Delinquency, he posits that control theories presume that deviant acts are committed when an individual�s bond to society is thin or broken, and he provides four elements which he believes are the main components of the societal bond (Hirschi, 2006). These components are attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief.

Attachment is related to the people one spends time with as well as the degree of intimacy connected to the relationship. Hirschi speculates that becoming separated from others may result from interpersonal conflict. In return, the conflict might build up to produce �socially derived hostility� that might explain the deviant acts that the individual with weak attachments commit (Hirschi, 2006). Also, the type of people to which one is attached may have an affect on whether or not one he or she will participate in deviant acts. For instance, if one is attached to conventional people, then he may be less likely to engage in deviant activities; however, if one is attached to unconventional people, then he may be more likely to engage in deviant activities.

Commitment is related to the investments or goals one becomes involved in. Hirschi reasons that when one is faced with the choice of whether or not to participate in deviant acts he must take into consideration the consequences that may affect his investments (Hirschi, 2006). In other words, if one is committed to conventional goals, then he may be less likely to engage in deviant activities than one who is either not committed to goals or who is committed to unconventional goals. Furthermore, it appears that most courses of action within society, such as educational and occupational goals, are normally conventional (Hirschi, 2006).

Involvement is related to the activities of which one decides to become a member. For most individuals, time and energy is spent participating in a myriad of activities, most of which tend to be conventional. It has been suggested in control theory that people may become engrossed in their conventional activities to the point that they may have no time to participate in deviant behavior (Hirschi, 2006). In other words, one is less likely to engage in deviant behavior if he is involved in conventional activities, and the more time he spends engaged in the conventional activities the less time he will have to engage in unconventional activities.

The final element of the bond, or belief, is related to value system of which a person is associated and the degree to which they consider these values true. These value systems are composed of rules which believers are expected to follow; however, according to Hirschi, those who break the rules, or participate in deviant behavior, nevertheless continue to believe in the rule even as he is breaking it (Hirschi, 2006). Moreover, it seems as though individuals who commit deviant acts may either view rules as mere words or rationalize their deviant behavior so it appears they are not in actuality going against the rule (Hirschi, 2006). For instance, one may choose to not steal because he believes stealing to be wrong, but another person who believes stealing is wrong and yet steals anyway may rationalize his actions by stating that the person he is stealing from actually owed him a debt.

A combination of the four bonds or lack there of may be a determining factor in whether or not a person may commit deviant acts. If a person does not have any conventional attachments, commitments, involvements, or beliefs, then it has been argued by control theorists that there is no reason to not engage in deviant acts. It has further been proposed that the stronger the four parts are, the stronger the bond which in turn may result in less reason a person has to commit acts of deviance.

Adolescent Violence. There is a plethora of information collected from studies regarding adolescent violence, including studies on the causes of such violence and the contributing factors. Violence in adolescent individuals should be considered a growing social trend of which the nation should be concerned (Wright & Fitzpatrick, 2006). In some cases, researchers have chosen to study specific forms of adolescent violence such as school violence. Factors including negative or distant relationships with teachers, a negative attitude toward institutions, such as schools (Ochoa, Lopez, & Emler, 2007), have been shown to have a negative significant effect on violent behavior in students; similarly, low academic performance may be a characteristic of schools with high rates of student violence (Limbos & Casteel, 2008). Wright and Fitzpatrick (2006) suggest that violence in school may decrease if the school emphasizes student socialization and participation in extra curricular activities.

Furthermore, it seems as though factors not relating to an adolescent�s school or education may also be issues associated with adolescent violence. For instance, an adolescent�s ethnic or racial identity may play a role in violent behavior. According to Choi, Harachi, Gillmore, and Catalano (2006), individuals who are of multiracial background exhibit more problem behaviors than those of monoracial families; the difference between the two groups might appear to be explained due to the disadvantages multiracial individuals are exposed to more often than monoracial individuals (Choi, Harachi, Gillmore, & Catalano, 2006). The same study also suggests that multiracial adolescents may be more sensitive to racial discrimination (Choi, Harachi, Gillmore, & Catalano, 2006), and therefore, it may be evident that the adolescents may retaliate against discrimination with violent acts.

Moreover, adolescent school violence has recently been positively correlated with the physical conditions of the adolescent�s neighborhood (Limbos & Casteel, 2008). According to Limbos and Casteel (2008), the presence of �visible graffiti, painted over graffiti, litter, cleanliness, dilapidated buildings, and dilapidated streets and sidewalks� (541) all may contribute to participation in violent school acts for the adolescents who live in the dilapidated neighborhoods. Furthermore, it seems as though religion may also be a factor when looking at violence in adolescence. For instance, Wright and Fitzpatrick (2006) reported that active involvement in neighborhood churches or other places of worship seemed to reduce the likelihood of adolescent violence. It may appear as if not only the beliefs and values of the adolescent�s religion play a role in stopping him from becoming violent but also the relationships within his religious setting; these relationships may include interactions with pastors, priests, deacons, youth group leaders, as well as congregation members.

Parent-Adolescent Relationship. The current study focuses on the effect that the parent-adolescent relationship has on violent behaviors in the adolescents. Throughout the years, research has suggested that the better and closer the relationship is between the child and his parent or parents the less likely he is to engage in violent behavior (Ochoa, Lopez, & Elmer, 2008; Silver, Field, Sanders, & Diego, 2000; Wright & Fitzpatrick, 2006; South, Krueger, Johnson, & Iacono, 2008; Howard, Lefever, Borkowski, & Whitman, 2006; Currie & Covell, 1998; Videon, 2002). The relationship between parent and child may also have an impact on other parts of the child�s life as well; for instance, according to Silver, Field, Sanders, and Diego (2000), the likelihood of depression, as well as self-harm, could also be tied to poor relationship characteristics. Moreover, adolescents who have not become violent, but are angry and scared of becoming violent, show similar patterns of poor communications with their parents (Silver, Field, Sanders, and Diego, 2000). It may also seem that the relationship can be reversed, or in other words, not only does the parent-adolescent relationship affect the child�s behavior, but the child�s personality can affect the parent-adolescent relationship (South, Krueger, Johnson, & Iacono, 2008).

Wright and Fitzpatrick (2006) report that certain aspects of the parent-adolescent relationship, such as interpersonal trust, involvement, and connection, are contributing factors in preventing adolescent violence. Additionally, the breakdown of the family structure might also be an important factor to consider in regards to causation of adolescent violence. In today�s society, divorce is a common occurrence; many times children of divorced parents are forced to live with one parent for the majority of the time or all of the time depending on the situation. It seems as if children living in two parent households may be more supervised; as a result, Currie and Covell (1998) found that the likelihood of living with both parents was extremely low in adolescents convicted of repeat offenses as compared to non-offenders. It also seems as though fathers and mothers may have different impacts on behavioral and violent problems in adolescents. Howard, Lefever, Borkowski, and Whitman (2006) reported that adolescents who live with their mothers but who also have consistent contact with their biological fathers were less likely to have behavioral problems.

Consequently, it may be evident that the satisfaction of parent-adolescent relationships before a divorce may contribute to behavioral problems after the divorce (Videon, 2002). For instance, Videon (2002) reported that adolescent males who described a high level of satisfaction in the relationship with their fathers showed an increase in delinquent behavior after moving in with their mothers after divorce while those with unsatisfactory relationships with their fathers showed less frequent instances of behavioral problems. The same study showed similar results for female adolescents and their mothers. Videon (2002) posited that being separated from the same-sex parent with whom an adolescent has a positive relationship will result in a greater likelihood of delinquency than those adolescents who reside with the same-sex parent with whom they have an insufficient relationship.

The current study attempts to analyze data gathered from high school students in an effort to research the relationship between parental involvement in a student�s life and violent behavior of the student. Based on past research as well as the author�s personal opinions, the following hypotheses were advanced: (H1) adolescents whose parents are highly involved in their lives will be less likely to commit violent acts than those adolescents whose parents are not involved in their lives, and (H2) adolescents whose parents have talked to them about drugs, sex, and alcohol will be less likely to commit violent acts than those adolescents whose parents have not talked with them about drugs, sex, and alcohol.

Method

Sample

The data used for the current study was taken from the Kentucky Youth Survey (KYS) and specifically from the information collected in the spring of 1996 (Wilcox & Clayton, 2001). Students from grades six through twelve in the most populous county in Kentucky were chosen; these students were from a total of 22 schools (Wilcox & Clayton, 2001). The total sample size was 13,349; however, due to nonresponse and missing data the total number of cases was reduced to 12,343 (Wilcox & Clayton, 2001). Furthermore, the final number of cases analyzed was cut down to 1500 cases.

Material and Procedure

Participants were asked to sign a consent form before completing the survey, and the consent form was issued to the students at the time of the administration of the questionnaires (Wilcox & Clayton, 2001). Parental consent was also required in order for the student to take part in the study (Wilcox & Clayton, 2001). A separate consent form explaining the study and the child�s selection was sent home to each parent; however, the parents were only asked to return the forms if they did not wish for their son or daughter to participate in the study (Wilcox & Clayton, 2001).

After the required consent had been given, participants were issued the KYS (Wilcox & Clayton, 2001). Teachers from the schools were asked to give out and collect the surveys during one class period during the day (Wilcox & Clayton, 2001). The KYS consists of 265 variables designed to questions participants on behaviors such as drinking, smoking, and drug usage as well as other delinquent activities (Wilcox & Clayton, 2001). Moreover, the survey also contains questions regarding students� �family background, attitudes toward school, involvement in school victimization and violence, peer behaviors, and religious attitudes� (Wilcox & Clayton, 2001, pg 520). The current study focused on specific variables concerning students� relationship with their parents and participation in violent activities or behaviors.

Independent Variables

Parental Involvement. To measure parental involvement, a ten-item scale was used. Respondents were asked to choose from a four-item Likert scale ranging from 1 �never� to 4 �most of the time.� The items included �how often my parent(s) seems to understand me,� �how often my parent(s) is concerned with how I am doing in school,� and �how often do I do things with my parent(s).� For a complete list of the ten items, please see Appendix A. An additive scale using the ten items (α=.74) was created with higher scores signifying higher levels of parental involvement.

Parental Communication. In order to assess the level of communication a student has with his or her parent(s), a seven-item scale was employed. Respondents were asked to answer either �yes� or �no� to each item. The items included �you and your parent(s) have ever talked about sex,� �you and your parent(s) have ever talked about birth control,� and �you and your parent(s) have ever talked about drug use.� For a complete list of the seven items, please see Appendix B. The seven items (α=.88) were combined into an additive scale with higher scores indicating higher levels of communication between students and parents.

Dependent Variables

Violent Acts. To assess violent acts, an eleven-item scale was used. Respondents were asked to answer either �yes� or �no� to each of the eleven items. The items included �have you ever shoved or tripped someone,� �have you ever been in a fist fight,� and �have you ever used a gun to threaten someone.� For a complete list of the eleven items, please see Appendix C. An additive scale was created using the eleven items (α=.84) with higher scores signifying higher participation in violent acts.

Controls. Three variables were used as controls so as to ensure that there was no spuriousness between parental involvement and violent acts as well as between parental communication and violent acts. Specifically the control variables were sex, age, and race.

Results

The mean score on the violence index for all participants was 4.36 out of a possible eleven points (See Table 1). The mean score of participants on the parental involvement index was 3.53 out of a possible five points, and the mean score on the parental communication scale was 4.18 out of a possible seven points. Table 1 depicts the complete list of descriptive statistics for all of the study variables.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables Descriptive Statistics

|

Variable |

Metric |

Mean |

S.D. |

Range |

|

Parent Involvement Index |

(0=No involvement, 5=Very High Involvement) |

3.53 |

.98 |

0-5 |

|

Parent Communication Index |

(0=No communication, 7=High communication) |

4.18 |

2.6 |

1-7 |

|

Violence Index |

(0=Not at all violent, 11=Extremely violent) |

4.36 |

2.92 |

1-11 |

|

Age of Respondent |

(Number of years) |

14.07 |

1.99 |

10-20 |

|

Sex of Respondent |

(0=female, 1=male) |

.51 |

.5 |

0-1 |

|

Race of Respondent |

(0=white, 1=nonwhite) |

.16 |

.36 |

0-1 |

n=1500

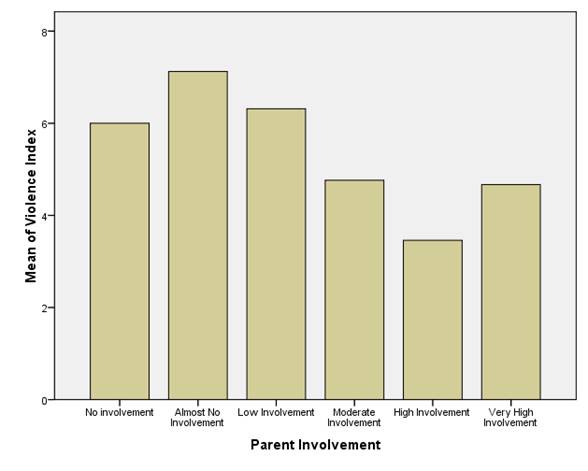

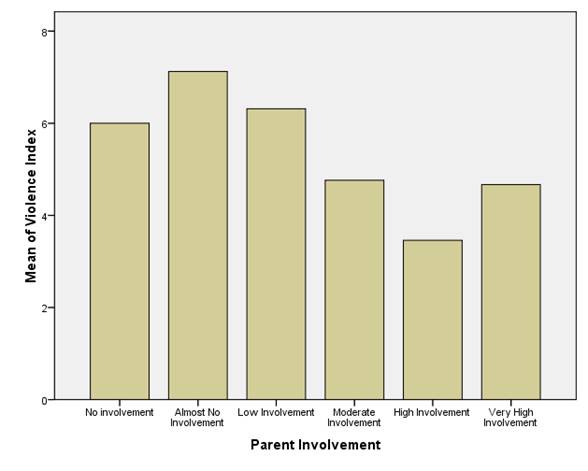

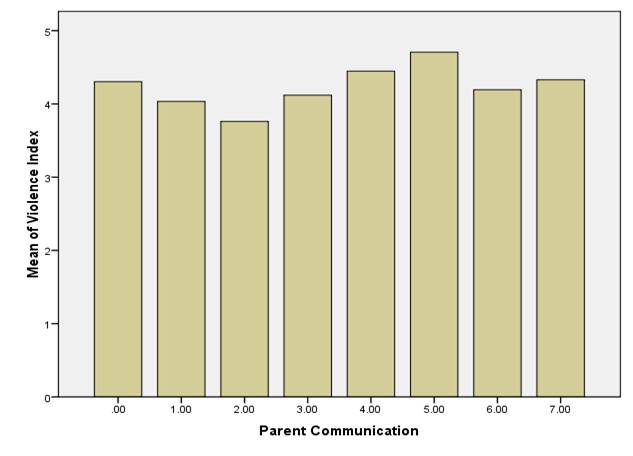

Table 2 displays the bivariate relationships between the study variables. A number of significant relationships were found among the variables suggesting both positive and negative correlations. However, the relationship between violence and parental communication failed to reach the level of significance. Furthermore, one of the most interesting significant relationships can be seen between violence and parental involvement. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show graphical representation of the relationships between parental involvement and violence and parental communication and violence respectively.

Table 2

Zero-Order Correlations among Study Variables

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1.Violence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Parental Involvement |

-.237* |

|

|

|

|

|

3. Parental Communication |

.030 |

.132 |

|

|

|

|

4. Age |

.056* |

-.124* |

.085* |

|

|

|

5. Sex |

.313* |

-.132* |

-.205* |

.009 |

|

|

6. Race |

.169* |

-.107* |

.036 |

.012 |

-.013 |

* p < .05

Figure

1

Figure

1

Parent Involvement and Violence

Figure 2

Parental Communication and Violence

In order to test the outcome of parental involvement on violence, a regression analyses was run controlling for age, race, and sex. The results indicated that a significant and negative relationship exists between the two variables. In other words, the more parents are involved in their children�s lives the less likely the children are to conduct violent acts. The results of the regression analysis can be seen in Table 3.

Furthermore, Table 3 also contains the results of a second regression analysis which was run to test the effect of parental communication on violence while controlling for age, race, and sex. The results of the second test indicate that the two variables are significantly and positively related. In other words, the results suggest that if parents talk to their children about issues such as drugs, sex, and alcohol, then their children are more likely to engage in violent acts.

Table 3

Regression Models Examining the Effects of Parental Involvement and Parental Communication on Adolescent Violence

|

|

Violence Coeff. S.E. |

N |

|

Parental Involvement |

-.588* .086 |

1126 |

|

Parental Communication |

.112* .032 |

1210 |

|

Age |

.038 .042 |

1354 |

|

Sex |

1.830* .166 |

1367 |

|

Race |

1.183* .232 |

1374 |

* p < .05 R2=.177

The results of the regression models seem to support one of the hypotheses in which it was suggested that more parental involvement in an adolescent�s life would reduce the likelihood of violent activity. However, the hypothesis that higher levels of parental communication would reduce the likelihood of adolescent violence was unsupported. The results seen in Table 3 seem to partially support the attachment aspect of Hirschi�s 1969 bonding theory due to the negative relationship between parental involvement and violence. On the other hand, the relationship between parental communication and violence seems to counter the same argument of the bonding theory.

Discussion

The two hypotheses of the current study were developed in an effort to investigate the relationship between parent-adolescent relationships and adolescent violence. The first hypothesis (H1) that adolescents whose parents are highly involved in their lives will be less likely to commit violent acts than those adolescents whose parents are not involved in their lives was supported by a significant negative relationship. Consequently, the second hypothesis (H2) that adolescents whose parents have talked to them about drugs, sex, and alcohol will be less likely to commit violent acts than those adolescents whose parents have not talked with them about drugs, sex, and alcohol was not supported. Interestingly enough, a significant positive relationship was found suggesting that in cases in which parents had talked to their children about drugs, sex, and alcohol the adolescents actually were more likely to participate in violent activities.

Although the current study found significant and interesting results, the outcomes may have been influenced by a number of limitations which future studies may benefit from fixing. The sample used in the current study consisted only of participants from one state which may have contributed to a homogenous population. The way children are raised in the particular area where the information was gathered may be different in a different region of the country. Therefore, the author suggests that future studies branch out into several areas of the country. Subsequently, the population also consisted of participants as young as age ten and with the majority in their early teenage years which may have impacted the results. For instance, participants may not have not yet engaged in violent acts. A thirteen year old participant may not have acted violently yet, but he or she may commit acts of violence within his or her next few years of adolescence. It seems as though it would be beneficial to seek out more participants who have completed adolescence.

A further limitation of the current study may involve the issue of peer influence. The current study did not take into consideration the effect of peer pressure and influence on an adolescent�s choice to participate in violent activities. In the years of adolescence, peer pressure appears to be a major contributing factor in the decision making processes of young teenagers, and as a result of that influence, a parent�s relationship with the adolescent may not be the strongest influence. Moreover, a father�s influence versus a mother�s influence was not taken into count. For instance, the difference between participants living with both parents versus one or the other was not considered as a factor in the analyses of the current study.

Past research seems to have mostly suggested that the better and stronger a parent-adolescent relationship is the less likely the adolescent is to commit acts of violence. However, the current study produced conflicting results. On the one hand, a parent�s involvement in an adolescent�s life seems to reduce violence, but on the other hand, communication involving sensitive issues, such as drugs and sex, between a parent and an adolescent may increase the likelihood of adolescent violence. Hirschi�s theory might be inclined to explain this inconsistency by taking into consideration the other attachments, commitments, involvements, and beliefs that an adolescent may have in his or her life. The researcher believes that research in this field could benefit parents as well as teachers and other authorities in the lives of adolescents. For instance, authorities such as parents and teachers may be able to better prevent adolescent violence if they are better able to understand the factors leading to such violence. Additionally, parents may be more inclined to connect with their children in a more productive manner knowing the possible prevention or contribution to violent tendencies.

An intriguing possibility for future studies would be to evaluate the effect that the study variable �parental communication� has on the participation in situation discussed by parents and adolescents. For instance, one component of parental communication was whether or not parents had talked to their children about sexual assault. It would be interesting to see if adolescents who had talked to their parents about sexual assault would be more or less likely to assault someone sexually. A simple idea for future studies could be to directly ask the participant to rate his or her relationship with his or her parents rather than issuing a scale to determine the strength of the relationship. In addition, involving the parents may also be an interesting addition to future studies. Perhaps parents may see their levels of involvement and communication in their children�s lives differently than how the adolescents perceive the levels of involvement and communication.

The primary findings of the current study involve aspects of parent-adolescent relationship and how those aspects relate to adolescent violence. Regardless of the limitations, the findings of the current study provide both support and for Hirschi�s (1969) bonding theory and an interesting discrepancy in regards to past research. Future research seems pertinent and could provide a better look into why adolescents turn to violence or even other forms of crime, but perhaps more importantly, the current study provides parents with information to influence their parenting choices and styles.

References

Choi, Y., Harachi, T.W., Gillmore, M.R., & Catalano, R.F. (2006). Are Multiracial Adolescents at Greater Risk? Comparisons of Rates, Patterns, and Correlates of Substance Use and Violence between Monoracial and Multiracial Adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(1), 86-97. Retrieved November 7, 2008 from PsycINFO database.

Currie, F. & Covell, K. (1998). Juvenile Justice and Juvenile Decision Making: Comparison of Young Offenders with Their Non-Offending Peers. The International Journal of Children�s Rights, 6, 125-136. Retrieved November 7, 2008 from Academic Search Premier database.

Hirschi, T. (2006). Control Theory of Delinquency. In Adler, P.A. & Adler, P., Constructions of Deviance: Social Power, Context, and Interaction, 5th edition (pp. 77-85). Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth.

Howard, K.S., Lefever, J.E., Borkowski, J.G., & Whitman, T.L. (2006). Fathers� Influence in the Lives of Children with Adolescent Mothers. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(3), 468-476. Retrieved November 7, 2008 from PsycARTICLES database.

Limbos, M. P. & Casteel, C. (2008). Schools and Neighborhoods: Organizational and Environmental Factors Associated with Crime in Secondary Schools. Journal of School Health, 78(10), 539-544. Retrieved November 7, 2008 from Academic Search Premier database.

Ochoa, G.M., Lopez, E.E., & Emler, N.P. (2007). Adjustment Problems in the Family and School Contexts, Attitude towards Authority, and Violent Behavior at School in Adolescence. Adolescence, 42(168), 779-793. Retrieved October 15, 2008 from Academic Search Premier database.

Silver, M.E., Field, T.M., Sanders, C.E., & Diego, M. (2000). Angry Adolescents who Worry About Becoming Violent. Adolescence, 35(140), 663-669. Retrieved October 15, 2008 from Academic Search Premier database.

Silver, M.E., Field, T.M., Sanders, C.E., & Diego, M. (2000). Angry Adolescents who Worry About Becoming Violent. Adolescence, 35(140), 663-669. Retrieved October 15, 2008 from Academic Search Premier database.

Videon, T.M. (2002). The Effects of Parent-Adolescent Relationships and Parental Separation on Adolescent Well-Being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 489-503. Retrieved November 7, 2008 from PsycINFO database.

Wilcox, P. & Clayton, R. (2001). A Multilevel Analysis of School-based Weapon Possession. Justice Quarterly, 18, 509-541.

Wright, D.R. & Fitzpatrick, K.M. (2006). Social Capital and Adolescent Violent Behavior: Correlates of Fighting and Weapon Use among Secondary School Students. Social Forces, 84(3), 1435-1453. Retrieved October 15, 2008 from Project MUSE database.

Appendix A

The following ten items were used to compose the Parental Involvement Index. Participants were asked to respond on a Likert Scale ranging from �never� to �most of the time.�

1. How often my parent(s) seems to understand me.

2. How often my parent(s) makes rules that seem fair to me.

3. How often my parent(s) knows where I am when I�m not at home.

4. How often my parent(s) knows who I am with when not at home.

5. How often my parent(s) is concerned with how I am doing in school.

6. How often I share me thoughts and feelings with my parent(s).

7. How often I feel unwanted by my parent(s).

8. How often I do things with my parent(s).

9. How often my parent(s) punishes me by scolding me.

10. How often my parent(s) punishes me by grounding me.

Appendix B

The following seven items were used to create the Parental Communication Index. Participants were asked to respond �yes� or �no.�

1. You and your parents have ever talked about sex.

2. You and your parents have ever talked about HIV/AIDS

3. You and your parents have ever talked about VD or STDs.

4. You and your parents have ever talked about birth control.

5. You and your parents have ever talked about pregnancy.

6. You and your parents have ever talked about sexual assault.

7. You and your parents have ever talked about drug use.

Appendix C

The following eleven items were used to create the Violence Index. Participants were asked to respond �yes� or �no� as to whether or not they have participated in any of the following.

1. Ever shoved or tripped someone.

2. Ever sat on someone or pinned someone down.

3. Ever hit, punched, or slapped someone with your hand or fist.

4. Ever hit someone with an object you were holding or threw.

5. Ever pulled, twisted, squeezed, or pinched part of other�s body.

6. Ever laid a trap for someone so he/she would get hurt.

7. Ever been in a fist fight.

8. Ever used a weapon during a fight.

9. Ever threatened to hurt someone with a weapon.

10. Ever been threatened with a gun.

11. Ever used a gun to threaten someone.

©