Figure

1

Figure

1Cassandra B.

Fremder

Abstract

The objective of this experiment was to determine if gender

or self-esteem contributed to the development of eating disorders. The study

involved a total of 100 students who participated by completing a survey used to

examine self-esteem, dietary habits, and experience with eating disorders.

Results found that participants who reported higher self-esteem also reported

less experience with eating disorders. Additionally, it was found that females

rated themselves lower for self-esteem and were more likely to report experience

with an eating disorder than did males. These results indicated a significant

correlation between self-worth and eating disorders, as well as a significant

correlation between gender and self-esteem, and gender and eating disorders.

Therefore, it can be said that both hypotheses were supported within this

sample, suggesting that students with high self-esteem are less likely to have

an eating disorder, and that women are more likely than men to suffer from

eating disorders.

Self-esteem is an important issue in eating disorders. It has been known

that gender, self-esteem, body image, and perceived self-worth seems to be

related to dietary habits and eating disorders; but researchers have wanted to

understand the relationship more clearly, comprehending the degrees to which

they interact with each other. Many research studies have presented the idea

that those who suffer from an eating disorder are more likely to have lower

self-esteem than those who do not have an eating disorder (e.g. de la Rie,

Noordenbos, & Furth, 2005; Hesse-Biber, Marino, Watts-Roy, 1999). These studies

and others have shown that eating disorders are associated with lower levels of

self-esteem and perception of self-concept. Additionally, research regarding the

impact of gender on self-esteem has continually supported the idea that women

are more likely than men to report lower levels of self-esteem and endorse

eating disorders (e.g. Green, Scott, Cross, Liao, Hallengren, Davids, & Jepson,

2009). Although much research has been conducted to show the degrees of relation

between self-esteem, gender, and eating disorders among various populations, few

studies have attempted to find these correlations among college students. The

motivation that prompted this research study was to determine if students with

higher self-esteem were less likely to develop eating disorders and to

understand the impact of gender on self-esteem and eating pathology.

For example, de la Rie, Noordenbos, and Furth (2005) sought to measure

the quality of life of eating disorder patients and former eating disorder

patients. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether the quality of

life differs between four diagnostic groups: anorexia nervosa patients, bulimia

nervosa patients, eating disorder not otherwise specified patients and former

eating disorder patients, and to understand what factors influence the quality

of life. To do this, the experimenters administered a generic health-related

quality of life questionnaire, the Short Form-36, and the Eating Disorder

Examination-Questionnaire to 156 eating disorder patients (44 anorexia nervosa

patients, 43 bulimia nervosa patients, 69 eating disorder not otherwise

specified patients) and 148 former eating disorder patients, all recruited from

different parts of the Netherlands by various means. A limitation of this study

was that participants were not asked to report on whether or not they had

comorbid disorders. Another limitation was that the advertisements to

participate in this study may have appealed especially to those who have

received treatment for eating disorders.

The results of the de la Rie, Noordenbos, and Furth (2005) study

indicated that eating disorder patients had significantly poorer quality of life

measures than the former eating disorder patients on the Short Form-36 subscales

of Physical Role Functioning, Emotional Role Functioning, Vitality, General

Health Perception, Social Functioning and Mental Health. Additionally, no

significant differences were revealed between eating disorder diagnostic groups

with regard to the quality of life, except on General Health Perception.

Anorexia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified patients reported

poorer quality of life than former eating disorder patients on General Health

Perception, but not bulimia nervosa patients. Higher self-esteem was associated

with a higher score on General Health Perception and with a higher score on

vitality. These findings presented that self-esteem showed the highest

association with the quality of life of both eating disorder patients and former

eating disorder patients.

Previous studies have sought to observe to correlations of self-worth and

eating disorders. On the contrary though, not many have researched these in

regard to college students. Hesse-Biber, Marino and Watts-Roy (1999) conducted a

longitudinal study to determine whether women in the college population who

suffered from eating disorders during their college years would recover during

their post-college years. The participants, who included 144 women in the

original population, were asked to answer questionnaires during their sophomore

and senior years of college. Later, the twenty-one participants that continued

for the duration of the six-year study were engaged in in-depth interviews that

covered a wide range of psychological, environmental, developmental, and

sociocultural factors. A limitation of this study was that the researchers

relied on qualitative data rather than hypothesis testing and replication of

past studies.

After the interview, participants

answered a short questionnaire, which dictated demographic information and used

continuum scales to measure eating patterns. The Eating Habits Scale consists of

five categories: normal eaters, normal dieters, presyndrome, at risk and problem

eaters. Women in the study were placed in these categories during three

different points in time: sophomore year, senior year, and two years

post-graduation. The Changes in Eating Habits Scale measured changes in

individual eating patterns from the sophomore year to the senior year and from

the senior year to two years post-graduation. It was designed to capture the

ways in which eating patterns could change. The researchers (Hesse-Biber, et

al., 1999) found that eleven women �got better�: that their disrupted eating

patterns in college returned to normal post-graduation, and that ten women

�remain at risk�: that they continue to exhibit tendencies toward disordered

eating and distorted body image. A pattern of healthy self-concept emerged for

the eleven women in the �got better� group; themes of their interviews were

confidence, autonomy, success in job and success in relationships. For those

that remain at risk, their relationships are described as tense, dissatisfaction

was reported in the autonomous realm, and the women expressed self-doubt and a

diminished self-esteem.

Another study (Green, Scott, Cross, Liao, Hallengren, Davids, Carter,

Kugler, Read, & Jepson, 2009) examined whether a unique relationship exists

between depression and eating disorder behaviors after controlling for

maladaptive social comparison, body dissatisfaction, and low self-esteem. The

participants were a volunteer sample with a total of 208 participants, with ages

ranged from seventeen to thirty-two years and body weights ranged from ninety to

345 pounds. Participants included 127 undergraduate women and eighty-one

undergraduate men who completed a demographic questionnaire, the Eating Disorder

Examination-Questionnaire, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, the Body Shape

Questionnaire � Shortened Version, the Social Comparison Rating Scale, and the

Beck Depression Inventory-II. The results indicated that undergraduate women

were more likely to endorse eating disorder pathology. Additionally, the

hypothesis was supported, that minimal unique variance was found in eating

disorder behaviors explained by depression after controlling for maladaptive

social comparison, body satisfaction, and low self-esteem. A limitation of this

study was its exclusive reliance on self-report measures and failure to

incorporate biological and sociocultural predictors.

There are many steps in recovery from an eating disorder, including

biological, psychological, social, behavioral, and emotional aspects.

Additionally, research by Bardone,-Cone, Schaefer, Maldonado, Fitzsimmons,

Hamby, Lawson, Robinson, Tosh, and Smith (2010) provides support that an

improved self-concept may be an integral part of full eating disorder recovery.

In an experiment that focused on measures of self-esteem, self-efficacy and

self-directedness, these researchers hypothesized that individuals fully

recovered from an eating disorder would have higher self-esteem, self-efficacy

and self-directedness than individuals partially recovered from an eating

disorder or those currently meeting criteria for an eating disorder.

Participants included ninety-six current and former female eating disorder

patients from the University of Missouri Pediatric and Adolescent Specialty

Clinic and sixty-seven healthy control participants who were aged sixteen and

older with no current or past eating disorder symptoms.

Participants were told to fill

out questionnaires and also participated in an interview, which operationalized

eating disorders using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Patient

Edition, the Eating Disorders Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation

Interview, the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire, and the Body Mass

Index. Self-concept was operationalized by using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem

Scale, the General Self-Efficacy subscale of the Self-Efficacy Scale, and the

Self-Directedness subscale of the Temperament and Character Inventory. Results

indicated that the healthy controls and fully recovered group did not differ

significantly in global self-esteem, self-efficacy, or self-directedness.

Additionally, the partially recovered group was not significantly different from

the active eating disorder group, although there was a marginally significant

difference (p = .06) for intimate relationships. The nature of this study made

the experimenters able to examine self-concept variables across various stages

of an eating disorder: active, partially removed, and fully recovered.

Ross and Wade (2004) presented a study in which they investigated

mediational processes by which variables may work together to increase the

likelihood of dietary restraint and uncontrolled eating, directed by the

framework suggested by the cognitive model. The researchers� sample consisted of

111 female college students aged between eighteen and twenty-five years, as this

is likely when eating disorders develop. A self-image questionnaire was

distributed to participants, who were asked to indicate the answer which was

true for them at that particular moment in time. Their individual Body Mass

Index was also calculated. Self-esteem was assessed using the State Self-Esteem

Scale (SSES), where lower scores are indicative of lower self-esteem. Concerns

about weight and shape, dietary restraint, and uncontrolled eating were measured

using the Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire, where higher scores are

indicative of higher degree of restrained eating behavior, and the Eating

Disorders Inventory-2, where higher scores are indicative of a higher degree of

uncontrolled eating behavior.

Results of this study indicated that BMI, externalized self-perception

and self-esteem together accounted for 54.9 per cent of the variance in

overvalued ideas about body weight and shape, thus self-esteem partially

mediated the relationship between externalized self-perception and a combined

measure of weight and shape concern. Self-esteem and weight shape concern

together accounted for 30.2 per cent of the variance in uncontrolled eating;

therefore, weight and shape concern fully mediated the relationship between

self-esteem and uncontrolled eating. Dietary restraint did not mediate the

relationship between weight and shape concern and uncontrolled eating.

In a study conducted by Tchanturia, Troop and Katzman (2002), 245 women

from Georgia completed a number of questionnaires to determine whether weight

and shape affect self-esteem and self-worth for women of non-Western countries

as much as it affects those of Western countries. The participants were

considered an �at-risk� sample for eating disorders, including participants

engaging in psychotherapy, patients at a somatic clinic, or women in a

diet/shaping club. The questionnaires, measuring eating pathology, anxiety and

depression, as well as two measures concerning their evaluation of weight and

shape in relation to self-esteem, were distributed to the participants. These

standardized tests included the Eating Attitudes Test, Bing Investigatory Test,

Edinburgh and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, a body dissatisfaction

scale using line drawings, and the Shape- and Weight-Based Self-Esteem Scale.

Both overvaluation of weight and shape and shape- and weight-based self-esteem

were significantly correlated with measures of eating deviations. In addition,

the 159 of the women desired a smaller body shape. However, despite these

associations, the overall degree to which women based their self-esteem on

weight and shape was less than that reported in Western-based studies.

Katsounari (2009) conducted a cross-cultural study to examine two

psychological variables � self-esteem and depression � and their relationship

with eating disturbance in two different cultural contexts, Cyprus and Great

Britain. Participants consisted of 140 randomly selected women, seventy from

Great Britain and seventy from Cyprus, who ranged from nineteen to twenty-five

in age and who were born and raised in Great Britain and Cyprus, respectively.

Selection criteria required the Cyprus females to be able to read English. It

was hypothesized that the women participants of Cyprus would have lower scores

in the self-esteem scale and higher scores in the depression scale, suggesting

higher disturbed eating attitudes than the British sample. Variables were

operationalized using the EAT-40 (Eating Attitudes Test), wherein participants

respond to forty questions on a six-point frequency scale (support to this

measure of assessment is present in both Western and non-Western populations),

the Beck Depression Inventory, which serves as the most prominent and frequently

cited self-report of depression, and the Battle Culture-Free Self-Esteem

Inventory for Adults, which measures perceived self-worth in three subscales:

general self-esteem, personal self-esteem, and social self-esteem; the order of

the questionnaires was counterbalanced to control for order effects.

The analysis of the data gained found that the average self-esteem score

for the British sample (M = 28.7) was higher than the average score reported for

the Cypriot sample (M � 25.620) indicating higher self-esteem for the British

participants. The average depression score for the British sample was lower (M =

5.3) than the Cypriot sample (M = 8.8) indicating that the Cyprus women had

higher depressive tendencies. The average EAT score for the British sample (M =

9.9) was lower than the Cypriot sample (M = 17.1) indicating more disturbed

eating behaviors than the British sample. For both samples, a positive

relationship was found between depression and eating disordered attitudes, which

was found to be significant.

On a more specific note, not many studies have focused on male

participation in studies measuring eating disorders and self-esteem. Even

further, a rare amount has included transsexual subjects, as most of the studies

seem to involve women only. One such study, (Vocks, Stahn, Loenser, & Legenbauer,

2009), attempted to discover whether people with Gender Identity Disorder (GID)

differed from controls of both sexes and people with eating disorders in terms

of the degree of eating and body image disturbance, self-esteem, and depression.

Participants consisted of 356 participants in total, including eighty-eight

self-identified male-to-female (MtF) transsexuals, forty-three female-to-male (FtM)

transsexuals, sixty-two females with an eating disorder, fifty-six male

controls, and 116 female controls. All of the participants completed the Eating

Disorder Examination Questionnaire, Eating Disorder Inventory, Body Checking

Questionnaire, Drive for Muscularity Scale, Rosenberg self-Esteem Scale, and

Beck Depression Inventory.

Results of the study conducted by Vocks (et al., 2009) indicated that MtF

participants showed higher scores on restrained eating, body shape concerns,

drive for thinness, bulimia, body dissatisfaction, and body checking compared to

male controls and even with some variables compared to female controls.

Additionally, FtM displayed a higher degree of restrained eating, weight

concerns, body dissatisfaction and body checking compared to male controls. Even

more, participants with GID showed higher depression scores than did the

controls, though no differences concerning drive for muscularity and self-esteem

were found. One implication of this study was that the participants were

self-identified transsexuals, not diagnosed by the researchers, so therefore it

cannot be known for certainty that each participant fully met the criteria for

GID according to the DSM-IV-TR. This study is important because it speculates

that people with GID might be at a higher risk of eating disorders, therefore

prevention programs should be implemented to help people with GID to avoid

developing an eating disorder.

Another study, conducted by Roberto, Grilo, Masheb, and White (2010),

aimed to compare bulimia nervosa, binge eating, and purging disorder on

clinically significant variables and examine the utility of once versus

twice-weekly diagnostic thresholds for disturbed eating behaviors. Participants

in the study consisted of 234 female community volunteers chosen from a total of

930 respondents who discovered the study through various websites. Participants

were asked to self-report on questionnaires including the Eating Disorder

Examination Questionnaire, the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire, which looks at

cognitive restraining, disinhibition of control over eating, and perceived

hunger, the Questionnaire for Eating and Weight Pattern-Revised, the Beck

Depression Inventory, The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and self-reported

demographic information, height and current weight were also collected.

The results of this study indicated that bulimia nervosa was a more

severe disorder than binge eating disorder and purging disorder. Additionally,

the three disorders differed significantly in self-reported restraint and

disinhibition; the bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder groups reported

higher levels of depression than those of the purging disorder. Also, for

bulimia nervosa, participants that engaged in behaviors twice-weekly rather than

once-weekly were more symptomatic in their responses.

In trying to examine the effects of anger, perfectionism, and exercise on

eating pathology among college women, Aruguete, Edman, and Yates (2012)

conducted a study involving 258 students of a California community college who

varied in ethnicity and were unaware of the purpose of the study. The procedure

involved a series of survey questions that measured trait anger and suppressed

anger, eating pathology, exercise commitment, and perfectionism. Trait anger was

measured using the State Trait Anger Expression Inventory and suppressed anger

by the Anger Discomfort Scale. Eating pathology was measured using the Drive for

Thinness Subscale of the Eating Disorder Inventory. Exercise commitment was

evaluated using the Commitment to Exercise scale and the Self-Loathing Subscale

of the Exercise Orientation Questionnaire. Lastly, perfectionism was assessed

using two subscales from the Multidimensional Perfectionism scale: Concern over

Mistakes Subscale and Parental Criticism Subscale.

After performing bivariate correlations to test whether anger,

perfectionism, and exercise commitment would be correlated with eating

pathology, Aruguete (et al., 2012) performed a series of linear regressions to

investigate the effects of anger on perfectionism, exercise commitment, and

eating pathology. The results indicated that exercise and perfectionism (but not

anger) showed significant associations with eating pathology. Additionally, they

found that anger did not independently predict eating pathology, but that trait

anger was negatively associated with exercise commitment and that anger would

independently predict perfectionism. This study supports pervious research,

although one limitation of this study was that it used a convenience sample that

consisted of mostly Asian/Pacific Islanders.

In an attempt to investigate the cross-cultural validity and reliability

of the Chinese Eating Disorder Examination (CEDE) in China, Jun, Jing, Jian,

Hong, Shu Fang, Xiao Yan, and Hsu (2011) conducted an experiment involving

forty-one eating disorder participants and 43 non-eating disorder control

participants of Mainland China. Each group included male and female

participants, and the mean age was 19.86. Though the Eating Disorder Examination

has been supported in prior research to be valid and reliable among Asian

cultures, the researchers sought to examine its reliability in a specific

population of central China after having it translated to Mandarin. The

researchers distributed the CEDE to all participants to evaluate the reliability

and validity in the study population. The reliability indicators were internal

consistency, inter-examiner reliability and test-retest reliability. The

validity indicators were content validity, criterion validity and discrimination

validity. The researchers found the internal consistency, test-retest

reliability, and inter-examiner reliability of the CEDE to be quite high,

indicating that the CEDE has high validity and reliability for the study of

eating disorders in Mainland China. Additionally, they found that the clinical

features of eating disorders among this population are essentially similar to

those of other cultures.

In another study, experimenters (Torres-McGehee, Monsma, Gay, Minton, &

Mady-Foster, 2011) sought to examine the pressures to be thin on female athletes

of appearance-based sports, particularly equestrian athletes. They wanted to

analyze the riding style of the athlete and academic status, along with

perceived body image disturbances. The study was cross-sectional and included

138 volunteer participants of seven universities throughout the United States. A

questionnaire was used to acquire basic and demographic data, such as academic

status and equestrian background, and participants also self-reported their

height, current weight, lowest weight, and ideal weight. Following, the

researchers administered two surveys via email to the participants. The first

was the Eating Attitudes Test, which was used to screen for eating disorder

characteristics and behaviors; the test includes three subscales: dieting,

bulimia, and food preoccupation and oral control. The second, the Figural

Stimuli Survey, was used to asses body disturbance based on perceived and

desired body images; the survey is a scale involving sex-specific body mass

index figural stimuli silhouettes associated with Likert-type ratings of oneself

against nine silhouettes. Chi-square analyses and multivariate analyses of

varies were run to examine the data. Based on the Eating Attitudes Test,

estimated eating disorder prevalence among the participants was 42.0% in the

total sample, 38.5% among English riders, and 48.9% among Western riders. The

experimenters found that no body mass index or silhouette differences were found

across academic status or riding style in eating disorder risk. Also, the

participants perceived their body images as significantly larger than their

actual sizes and wanted to be significantly smaller in everyday clothing and

competitive uniforms.

Recently, descriptive research was conducted by Mond, Peterson, and Hay

(2010) to understand the prior occurrence of regular extreme weight-control

behaviors among women with binge eating disorder. The study involved

twenty-seven women who reported current regular binge eating episodes in the

absence of current regular extreme weight-control behaviors. For each behavior

assessed, participants were first asked whether they had ever engaged in that

behavior, and a positive response to the initial question was followed by a

series or related questions, including whether the behavior was regular. For

this study, �regular� was defined as �on average at least weekly for a period of

three months or more�, and �excessive� as �on average three or more times per

week for a period of three months or more�. Those

who reported the behavior to be a regular occurrence were further asked

questions about the age at which it first occurred and the actual frequency of

the behavior.

Results of this study indicated

that approximately two thirds of participants (65.4%) reported either one or

more purging behaviors at least weekly or one or more non-purging behaviors at a

frequency deemed �excessive� by definition; 38.5% of participants reported

either purging behaviors at least twice weekly or non-purging behaviors five or

more times per week for a period of three months or more. Additionally, five of

the participants had met criteria for bulimia nervosa outlined in the Eating

Disorder Examination, and three of these five participants met criteria for

bulimia nervosa as outlined in the DSM-IV. As for confidence in their

recollections, 38.7% reported to be very confident, 29.0% reported to be

extremely confident, 25.8% reported to be moderately confident, and 6.5%

reported to be a little confident. One implication of this study is that there

may be a considerable overlap between bulimic eating disorders characterized by

binge eating and those characterized by extreme weight-control behaviors.

Previous research has indicated

that body awareness can have an effect on the symptoms of eating disorders. For

instance, in a study conducted by Catalan-Matamoros, Helvik-Skjaerven,

Labajos-Manzanares, Mart�nez-de-Salazar-Arboleas, and S�nchez-Guerrero (2011),

twenty-eight outpatients with eating disorders for less than five years were

treated with body awareness therapy for seven weeks to analyze the feasibility

of improved body awareness in lessening the symptoms of eating disorders. The

participants were randomly assigned into one of two groups: an experimental

group (n=14) and a control group (n=14). The trial consisted of three phases:

the pre-test in which participants from both groups were assessed, the

intervention in which participants in the experimental group received basic body

awareness therapy for seven weeks through twelve sessions, and the post-test in

which participants from both groups were assed at the end. Assessments used in

the pre- and post-tests included the Short Form-36 to assess quality of life,

the Eating Disorder Inventory to

assess the psychological and behavioral common traits in anorexia nervosa and

bulimia, and the Eating Attitude Test-40 to measure symptoms and concerns

characteristic of eating disorders. Data was analyzed to understand the

comparison between the effects produced in the dependent variables of the

experimental and control groups. The results indicated that significant

differences were found in Eating Disorder Inventory and its subscales (mean

difference: 26.3; P=0.015), in Body Attitude Test (mean difference 33.0;

P=0.012), Eating Attitude Test-40 (mean difference: 17.7; P=0.029), and in the

Short Form-36 in the mental health section (mean difference: 13; P=0.002). This

study found that there is some effectiveness of basic body awareness therapy in

improving some symptoms in outpatients with eating disorders; also, that it

heightens the ability to get well, especially in preventing relapses.

In a qualitative research study conducted by Rance, Moller, and Douglas

(2010), seven female counselors who had recovered from eating disorder pasts

participated in semi-structured interviews to examine countertransference

experiences in relation to their body image, weight, and food pathology, their

perceptions about the impact of such experiences and their beliefs about the

effects of their own eating disorder history. The data collection involved

interviews that allowed for the unique, personal experiences of the counselor

while ensuring the areas of interest in the research project were covered. Data

was analyzed by guidelines that focused on themes and connecting features; the

identified themes were ordered in a master table and were: �double-edged

history,� which characterized a common problem faced by the participants,

�emphasis on normality�, which describes a strategy of normalization to overcome

this problem, and the theme of �selective attention�, which illustrates a number

of cognitive and attention strategies employed to enact this solution.

�Double-edged history� illustrated the participants� awareness of both the

benefits and dangers of their eating disorder past. Results of this study shed

light upon an unexplored aspect of the personal and professional experiences of

eating disorder counselors with an eating disorder past. The three themes

illustrate a complex interwoven triad of problem, solution and strategy. The

results suggested that counselors; experienced their eating disorder as a

positive and negative that led them to engage in a number of self-presentational

activities.

Many standard instruments of measure for eating disorders exist, such as

the Eating Disorder Inventory and the Eating Disorder Examination, although

rarely are they examined for applicability among specific populations. In an

attempt to analyze the dimensionality of three versions of the Eating Disorder

Inventory (EDI) in adolescent girls, Garc�a-Grau, Fust�, Mas, G�mez, Bados, and

Salda�a, C (2010) conducted a study involving 738 female adolescents aged

between fourteen and nineteen; the mean age was 15.91 years. The Spanish

adaptations of the Eating Disorder Inventory-1, 2 and 3 were used to assess

psychological, behavioral and affective characteristics related to eating

disorders, although conceptual and structural changes exist between the factors

of the EDI-3 and EDI-2. Goodness of fit and chi-squared tests were employed in

analysis of the data. The results of this study indicated that the dimensional

structure of the three versions of the Eating Disorder Inventory was not clearly

confirmed, at least in this particular sample. However, the shortened version of

the EDI-2 used in this study may be more suitable for use with adolescent girls

in the general population than the original questionnaire.

Sallet, Alvarenga, Ferr�o, de mathis, Torres, Marquess, and

Fleitlich-Bilyk (2010) executed a study to evaluate the prevalence and

associated clinical characteristics of eating disorders in patients with

obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) by comparing 815 patients with OCD in a

cross-sectional study. The researchers had three hypotheses: that OCD patients

with comorbid eating disorders would be more frequently women with early onset

of illness and severity of symptoms, have higher prevalence and severity of

contamination obsessions and cleaning compulsions, and show higher rates of

comorbid impulse control orders and body dysmorphic disorder. Assessment was

conducted via structured interviews with mental health professionals with

experience working with OCD and via standardized instruments, such as the

Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive

Compulsive Scale (DY-BOCS), Yale Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Natural history

Questionnaire, Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS), Beck Depression and

Anxiety Inventories, and the Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI); there were

no self-report assessments.

Results indicated that ninety two

patients (11.3%) presented the following eating disorders: binge-eating

disorders (59, 7.2%), bulimia nervosa (16, 2.0%), or anorexia nervosa (17,

2.1%). Compared to OCD patients without eating disorders, comorbid OCD-eating

disorder patients were more likely to be women with previous mental health

treatment. Additionally, assessment scores were similar within groups; however,

comorbid OCD-eating disorder patients showed higher lifetime predominance of

comorbid conditions, higher anxiety and depression scores, and higher frequency

of suicide attempts than did the OCD group without eating disorders. OCD-eating

disorder patients may be associated with �higher clinical severity.�

Persons with Borderline Personality disorder often struggle with poor

self-esteem. In a unique study conducted by Zanarini, Reichman, Frakenburg,

Reich, and Fitzmaurice (2010), researchers attempt to describe the longitudinal

course of eating disorders in patients with borderline personality disorder. The

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R axis I Disorders (SCID-1), the

Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) and the Diagnostic

Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (DIPD-R) were administered to 290

borderline inpatients and seventy-two participants with other axis II disorders

during their index admission and at five contiguous two-year follow-up periods.

Participants had a mean GAF score of

39.8, indicating major impairment in several areas. Results of the study

indicated that the prevalence of anorexia, bulimia and eating disorder not

otherwise specified declined significantly over time for those in both study

groups; however, the prevalence of eating disorder not otherwise specified

remained significantly higher among borderline patients. Over 90% of borderline

patients meeting criteria for one of the eating disorders experienced a stable

remission by the time of the ten-year follow-up, although diagnostic migration

was common. Additionally, both recurrences and new onsets of eating disorder not

otherwise specified were more common among borderline patients than recurrences

and new onsets of anorexia nervosa and bulimia.

In a study assessing the quality of life, course and predictors of

outcomes in community women with eating disorders not otherwise specified and

common eating disorders, researchers (Hays, Buttner, Mond, Paxton, Rodgers,

Quirk, & Darby, 2010) sought to describe the functional and symptomatic outcome

these women. The researchers investigated the two-year course and supposed

predictors of outcome of eighty-seven young community women with common eating

disorders following a health literacy (informational) intervention; the health

literacy intervention was provided randomly to half participants at baseline and

half at one year. The instruments of assessment included the Eating Disorder

Examination, the Short Form-12 Health Status Questionnaire, Kessler-10 for

general psychiatric symptoms, and the Defense Style Questionnaire. During the

follow-up assessments, researchers measured alcohol and substance misuse and

distributed the Life Events Checklist to indicate if the participant has

experienced a variety of life events over the last twelve months. Results of

multiple linear regression analyses indicated that eating disorder

psychopathology remained high and mental health quality of life remained poor.

For multivariate models, a higher baseline level of immature defense style

significantly predicted higher levels of eating disorder symptoms as well as

poorer mental health quality of life. Also, in line with the research conducted

by de la Rie (et al., 2005), women with common eating disorders followed to two

years continued to be highly symptomatic and have poor quality of life.

A similar study, conducted by Mu�oz, Quintana, Hayas, Aguirre, Padiema,

and Gonz�lez-Torres (2009) aimed to evaluate and compare the quality of life in

patients with eating disorders and general population, using the

disease-specific Health-Related Quality of Life for Eating Disorders (HeRQoLED)

questionnaire. Participants consisted of 358 patients with eating disorders who,

upon inclusion into the study, were sent three measurement instruments: the

HeRQoLED, the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) and the Short Form-12. Each patient

took part in psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic treatment programs, and

after one year of treatment and follow-up, the three questionnaires were sent

again to the participants. Univariate analysis was performed to determine which

variables were predictive of change in each of the HeRQoLED domains after one

year of treatment, and general linear models were performed to establish

variables for the multivariate analysis. Results indicated that patients with

anorexia nervosa had higher baseline scores (indicating worse perception of

quality of life on the HeRQoLED questionnaire and experienced smaller

improvements that patients with other eating disorder diagnoses after one year

of treatment. Body-mass index and EAT-26 scores were associated with changes in

quality of life. Short Form-12 scores showed significant improvement in the

physical component but not in mental health. Additionally, quality of life in

patients with eating disorders improved after one year of treatment, though it

did not reach the values of the general population.

In the current study, the researcher wanted to understand the

relationship and interactions between self-esteem, gender, and eating disorders.

The objective was to replicate similar studies to determine if having low levels

of self-esteem or self-worth contributed to the development of eating disorders

and whether or not gender impacted the prevalence of eating disorders. It was

hypothesized that students with high self-esteem were less likely to suffer from

eating disorders, including binge eating, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia nervosa.

The independent variable is self-esteem, which was measured by asking the

student participants questions regarding their self-worth and feelings towards

themselves. The dependent variables are the eating disorders: bulimia nervosa,

anorexia nervosa and binge eating. Another hypothesis was that women are more

likely than men to suffer from eating disorders, where gender is the independent

variable, and suffering from an eating disorder is the dependent variable.

Eating disorders were evaluated by asking the student participants questions

about their eating, exercising, dietary habits, and experience with eating

disorders. Body type was also evaluated by asking the participants to select one

of the given categories on the survey for themselves and for members of their

immediate family; the categories consist of different body shapes such as

underweight, average, or overweight. The survey consists of fifty-three

questions in total, including demographic information, Likert scales, the

categorical response of body type, and yes or no questions. It was hypothesized

that students that have or have had an eating disorder are more likely to report

low levels of self-esteem and that women are more likely than men to suffer from

eating disorder.

Method

Participants

A sample of 100 college students

was randomly selected from a small, private, liberal arts college in the midwest.

There were 45 males, 52 females, and 3 participants that did not report a

gender. Participants included 21 freshmen, 29 sophomores, 23 juniors, 17

seniors, 2 students in their fifth year or more, and 8 participants that did not

report their year in school. Participation was a convenience sample and

participants had the choice to withdraw at any point in time. The classes in

which the surveys were distributed were: Introduction to Psychology, Victorian

English Literature, Introduction to Ethics, and Introductory Biology.

Materials

The survey was designed by the

researcher with questions adapted from the Index of Self-Esteem (ISE) and

consisted of a questionnaire using 53 close-ended questions, presented using

constancy. The survey included questions about eating habits, the participants�

body shape, how the participants feel about themselves, and other items relating

to experience with eating disorders. Other questions included demographic

information, such as gender, year in school, and body type. All 100 surveys that

were distributed were returned, which may aid in the validity of this research.

Procedure

The surveys were distributed in classrooms based on a convenience sample.

Participants were asked to complete every question of the survey and were

instructed to ask the researcher if there were any questions. The questions

referring to self-esteem and dietary habits were designed to measure how the

participants feel about themselves (their perceived self-esteem) and whether or

not their eating pathology predisposed them to weight concern or an eating

disorder. The eating disorder items served to determine outright whether or not

the participants had prior exposure to eating disorders either through their

friends or personal experience. Surveys were completely anonymous; participants

signed their initials and dated the consent form, which they handed in

separately from the survey (see appendix). The survey was field tested in a

classroom of psychology majors studying experimental psychology, revised, and

was submitted to McKendree University�s Institutional Review Board along with

the purpose of research, hypotheses, and an agreement to abide by ethical

principles of research with human participants. It received Institutional Review

Board approval, valid for one year until March 8, 2013, exempt from IRB review

for its anonymity and data from consenting adult college students. Ethical

guidelines outlined by APA were followed. Statistical tests conducted to analyze

data include one-way ANOVAs, independent samples t-tests, and correlation

analyses to determine results.

Results

Figure

1

Figure

1

Figure 2

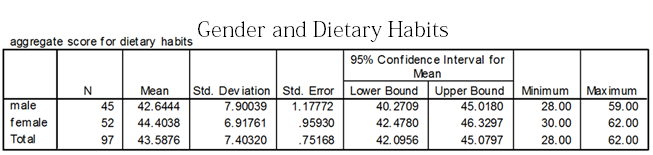

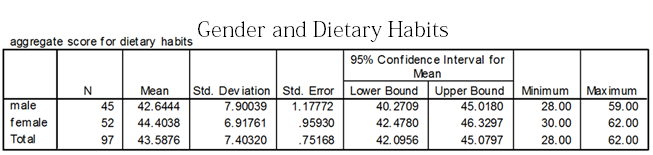

Figures 1 and 2 show the results

in using a one-way ANOVA to test whether gender has an impact on dietary habits.

Results indicated no significant difference in dietary habits based on gender, F

(1, 95) = 1.368, p = 0.245. Statistically, females were no more likely than

males to endorse healthier eating patterns.

Figure 3

Figure 4

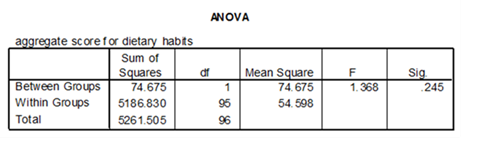

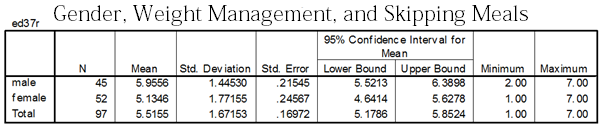

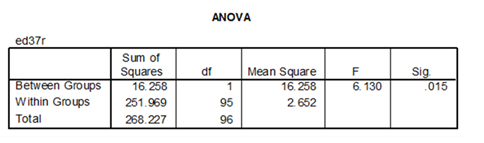

Figures 3 and 4 show the results

in using a one-way ANOVA to test whether gender influences meal skipping in an

effort engage in weight management. Results indicated a significant difference

in meal skipping to engage in weight management based on gender, F (1, 95) =

6.130, p = 0.015. It was found that more often than males, females reported that

they skip meals to engage in weight management.

Figure

5

Figure

5

Figure 6

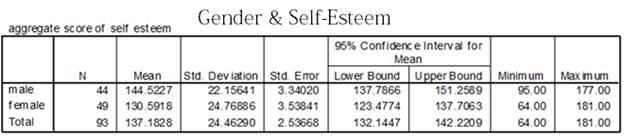

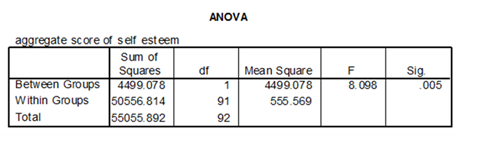

Figures 5 and 6 show the results

in using a one-way ANOVA to test whether gender has an impact on a person�s

self-esteem. Results indicated a significant difference in self-esteem based on

gender, F (1, 91) = 8.098, p = 0.005. It was found that females reported lower

levels of self-esteem than did males.

Figure

7

Figure

7

Figure 8

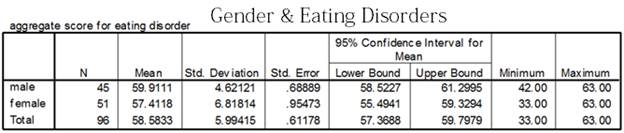

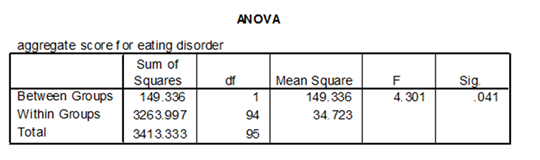

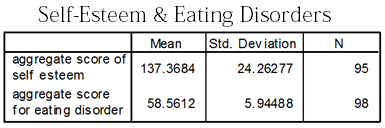

Figures 7 and 8 show the results

in testing the hypothesis that gender impacts an individual�s experience with

eating disorders by using a one-way ANOVA. Results indicated a significant

difference in experience with eating disorders based on gender, F (1, 94) =

4.301, p = 0.041. Statistically, females were more likely than males to report

experience with eating disorders, including bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa,

or binge eating.

Figure 9

Figure

10

Figure

10

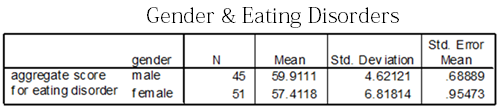

Figures 9 and 10 show the results in again testing the hypothesis that

gender impacts an individual�s experience with eating disorders by using an

independent samples T-test. The independent samples T-test analysis comparing

scores for males and females on eating disorders indicated that female scores (M

= 59.9, SD = 4.62) differed significantly from male scores (M = 57.4, SD =

6.82), t(94) = 2.074, p = 0.0205.

Figure 11

Figure 12

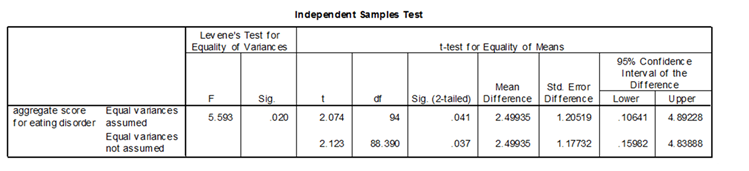

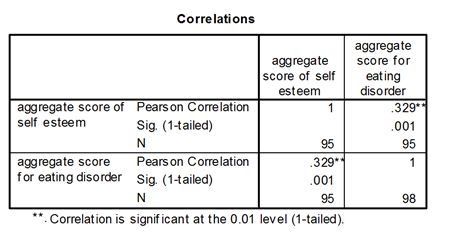

Figures 11 and 12 show the results in testing the hypothesis that

self-esteem is directly related to the development of an eating disorder by

using a correlation analysis. A Pearson�s Bivariate Correlation found a

significant relationship between self-esteem and eating disorders, (r = 0.329, p

= 0.001). It was found that participants who reported higher self-esteem also

reported less experience with eating disorders.

Discussion

The current research study can relate to a significant amount of other

studies that have sought to examine the interactions between self-esteem,

gender, and eating disorders. This study stands out from the others in that it

sought to examine the correlation between gender and self-esteem, gender and

eating disorders, and self-esteem and eating disorders. Though no solution was

found through the current study to diminish the prevalence of eating disorders,

awareness of the correlations between self-esteem, gender, and eating disorders

may prompt further research in finding how to improve self-esteem and minimize

eating disorders among college students, especially females.

While intriguing results,

implications, and correlations were found, limitations were present as well. One

limiting factor that may have affected the results was the small, convenience

sample size of participants, which did not allow for a full representation of

all college students. A larger sample size across a wider spread of campuses

would provide higher validity than did the current study. Additionally, the

survey should have included further demographic information, such as age, for

descriptive statistical purposes, and questions about the standard of body image

regarding gender.

The first prediction was that students with high self-esteem are less

likely to suffer from eating disorders, including binge eating, bulimia nervosa,

and anorexia nervosa. The results showed that there was a statistically

significant difference in that those who reported higher self-esteem also

reported less experience with eating disorders. This could be because those with

a higher sense of self-worth may not have as many body image issues and may

endorse a healthier eating pathology. Results of previous research studies (e.g.

Ross & Wade, 2004) indicated that self-esteem and weight shape concern together

accounted for about one-third of the variance in uncontrolled eating.

Another hypothesis that was presented prior to research was that women

are more likely than men to suffer from eating disorders. The results indicated

a statistically significant relationship between gender and eating disorders,

where females rated themselves lower for self-esteem and were more likely to

report experience with an eating disorder than did males. This could be because

society and the media instill a higher standard of body shape and image in

females at a young age than in males, which becomes impressed in how they view

themselves as adults. Many females struggle with body image expectations

throughout their lifetime, which may lead to the development of specific eating

and exercise pathologies.

It is worth noting that although both hypotheses were supported, results

indicated no significant difference in dietary habits based on gender. The

significant results of the current study may lead to new directions for this

research in the future. Perhaps further studies will begin to explore the impact

of gender and body expectations on self-esteem and eating disorders in the

college population. Subsequent research could lead to a greater understanding of

the factors that influence gender-specific body expectations, self-esteem, and

eating disorders; this could result in efforts to improve self-esteem and

minimize eating disorders among college students, especially those that are

female. There are many dangers related to eating disorders and low self-esteem,

especially during college, when students seem to be more vulnerable and critical

of themselves. The current study is intriguing and can most certainly add

validity to previous research and also advance towards new findings in the

future.

References

Aruguete, M.

S., Edman, J. L., & Yates, A. (2012). The Relationship between Anger and other

Correlates of Eating Disorders in Women. North American Journal Of Psychology,

14(1), 139-148.

Bardone-Cone,

A. M., Schaefer, L. M., Maldonado, C. R., Fitzsimmons, E. E., Harnby, M. B.,

Lawson, M. A., & � Smith, R. (2010). Aspects of Self-Concept and Eating Disorder

Recovery: What Does the Sense of Self Look Like When an Individual Recovers from

an Eating Disorder?. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 29(7), 821-846.

Catalan-Matamoros, D., Helvik-Skjaerven, L., Labajos-Manzanares, M., Mart�nez-de-Salazar-Arboleas, A., & S�nchez-Guerrero, E. (2011). A pilot study on the effect of Basic Body Awareness Therapy in patients with eating disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 25(7), 617-626.

De la Rie, S. M., Noordenbos, G., & van Furth, E. F. (2005). Quality of Life and Eating Disorders. Quality of Life Research, Vol. 14.

Garc�a-Grau,

E., Fust�, A., Mas, N., G�mez, J., Bados, A., & Salda�a, C. (2010).

Dimensionality of three versions of the eating disorder inventory in adolescent

girls. European Eating Disorders Review, 18(4), 318-327.

Green, M. A., Scott, N. A., Cross, S. E., Liao, K., Hallengren, J. J., Davids, C. M., & ... Jepson, A. J. (2009). Eating disorder behaviors and depression: a minimal relationship beyond social comparison, self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(9), 989-999.

Hay, P.,

Buttner, P., Mond, J., Paxton, S. J., Rodgers, B., Quirk, F., & Darby, A.

(2010). Quality of life, course and predictors of outcomes in community women

with EDNOS and common eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 18(4),

281-295.

Hesse-Biber, S., Marino, M., & Watts-Roy, D. (1999). A Longitudinal Study of Eating Disorders among College Women: Factors That Influence Recovery. Gender and Society, Vol. 13.

Jun, T., Jing, S., Jian, W., Hong, Z., Shu Fang, Z., Xiao Yan, W., & Hsu, L. (2011). Validity and reliability of the Chinese language version of the eating disorder examination (CEDE) in mainland China: Implications for the identity and nosology of the eating disorders. International Journal Of Eating Disorders, 44(1), 76-80.

Katsounari, I. (2009). Self-esteem, depression and eating disordered attitudes: A cross-cultural comparison between Cypriot and British young women. European Eating Disorders Review, 17(6), 455-461.

Mond, J. M., Peterson, C. B., & Hay, P. J. (2010). Prior use of extreme weight-control behaviors in a community sample of women with binge eating disorder or subthreshold binge eating disorder: A descriptive study. International Journal Of Eating Disorders, 43(5), 440-446.

Mu�oz, P. P., Quintana, J. M., Hayas, C., Aguirre, U. U., Padierna, A. A., & Gonz�lez-Torres, M. A. (2009). Assessment of the impact of eating disorders on quality of life using the disease-specific, Health-Related Quality of Life for Eating Disorders (HeRQoLED) questionnaire. Quality Of Life Research, 18(9), 1137-1146.

Rance, N. M., Moller, N. P., & Douglas, B. A. (2010). Eating Disorder Counsellors With Eating Disorder Histories: A Story of Being 'Normal'. Eating Disorders, 18(5), 377-392.

Roberto, C. A., Grilo, C. M., Masheb, R. M., & White, M. A. (2010). Binge eating, purging, or both: Eating disorder psychopathology findings from an internet community survey. International Journal Of Eating Disorders, 43(8), 724-731.

Ross, M., & Wade, T. D. (2004). Shape and weight concern and self-esteem as mediators of externalized self-perception, dietary restraint and uncontrolled eating. European Eating Disorders Review, 12(2), 129-136.

Sallet, P. C., de Alvarenga, P., Ferr�o, Y., de Mathis, M., Torres, A. R., Marques, A., & ... Fleitlich-Bilyk, B. (2010). Eating disorders in patients with obsessive�compulsive disorder: Prevalence and clinical correlates. International Journal Of Eating Disorders, 43(4), 315-325.

Tchanturia, K., Troop, N. A., & Katzman, M. (2002). Same pie, different portions: shape and weight-based self-esteem and eating disorder symptoms in a Georgian sample. European Eating Disorders Review, 10(2), 110-119.

Torres-McGehee,

T. M., Monsma, E. V., Gay, J. L., Minton, D. M., & Mady-Foster, A. N. (2011).

Prevalence of Eating Disorder Risk and Body Image Distortion Among National

Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Varsity Equestrian Athletes. Journal

Of Athletic Training, 46(4), 431-437.

Vocks, S., Stahn, C., Loenser, K., & Legenbauer, T. (2009). Eating and Body Image Disturbances in Male-to-Female and Female-to-Male Transsexuals. Archives Of Sexual Behavior, 38(3), 364-377.

Zanarini, M.

C., Reichman, C. A., Frankenburg, F. R., Reich, D., & Fitzmaurice, G. (2010).

The course of eating disorders in patients with borderline personality disorder:

A 10-year follow-up study. International Journal Of Eating Disorders, 43(3),

226-232.

APPENDIX A

Read this consent form. If you have

any questions ask the experimenter and

She will answer your questions.

�I have read the statement below and have been fully advised of the procedures

to be used in this project. I have

been given sufficient opportunity to ask any questions I had concerning the

procedures and possible risks involved.

I understand the potential risks involved and I assume them voluntarily.�

Please sign your initials, detach below the dotted line, and continue with the

survey.

Sign your initials here_________________

Date__________

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The McKendree University Psychology Department supports the practice of

protection for human participants participating in research and related

activities. The following

information is provided so that you can decide whether you wish to participate

in the present study. Your

participation in this study is completely voluntary.

You should be aware that even if you agree to participate, you are free

to withdraw at any time, and that if you do withdraw from the study, your

grade in this class will not be affected in any way.

This survey is being conducted to assist the researcher in fulfilling

a partial requirement for PSY 496W.

You must be over 18 years of age to participate in the survey.

It should not take more than 10 minutes for you to complete and will be

completely anonymous and confidential.

If you should have any other questions, don�t hesitate to contact me,

Cassandra Fremder, 618-830-7052 or at cbfremder@mckendree.edu, or Dr. Bosse,

618-537-6882 or at

mbosse@mckendree.edu.

Some of the questions in the survey may confront sensitive topics.

If answering any of these questions causes you problems or concerns,

please contact one of our campus psychologists, Bob Clipper or Amy Champion-Stahlman,

at 537-6503.

Rev. 3/31/09

APPENDIX B

STUDENT SURVEY

Gender: Male _____

or

Female ���_____

Year in School:

Freshman

Sophomore

Junior

Senior

5th Year or more

1. Please indicate your family�s body builds with an X. (Use additional X�s for

multiple siblings.)

Underweight

Average

Overweight

Mother:

_____

_____

_____

Father:

_____

_____

_____

Sister(s):

_____

_____

_____

Brother(s):

_____

_____

_____

Self:

_____

_____

_____

Please respond to numbers 2- 45 based on the following scale:

1 - Never

2 - Almost Never

3 - Rarely

4 - Sometimes

5 - Frequently

6 - Almost Always

7 � Always

(Please circle only one.)

2. I snack with healthy food.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Never

Almost Never

Rarely

Sometimes

Frequently

Almost Always

Always

3. I count calories.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

4. I rely on other people to feel good about myself.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

5. I exercise on a regular basis.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

6. I am on a diet/dieting.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

7. I feel good about myself.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8. I eat a lot of vegetables.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

9. I depend on others for attention.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Never

Almost Never

Rarely

Sometimes

Frequently

Almost Always

Always

10. I worry about my appearance.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

11. I eat a lot of junk food.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

12. I eat breakfast.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

13. I eat at least three balanced meals a day.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

14. I worry about my weight.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

15. I feel as if I am in control of my decisions and actions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

16. I feel healthy.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

17. I feel dependent on others.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

18. I think that I am a dull person.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

19. I like my body.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

20. I am concerned if other people like my body.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

21. I drink beer or alcohol.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

22. I eat a lot of fruit.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

23. I consume drinks high in sugar.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

24. I smoke.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Never

Almost Never

Rarely

Sometimes

Frequently

Almost Always

Always

25. I feel that people would not like me if they really knew me well.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

26. When I am with other people, I feel they are glad I am with them.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

27. I feel that I am a very competent person.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

28. I think I make a good impression on others.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

29. I feel that I need more self-confidence.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

30. I stare into mirrors and windows to see what I look like.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

31. I believe that other people are staring at me when I walk into a room.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

32. I would say I am obsessed with what my body looks like.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

33. I have confidence in myself.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

34. I am confident about my body.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

35. I have high self-esteem.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

36. I like what I see when I am looking in a mirror.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

37. I have skipped meals before to engage in weight management.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

38. I feel that others have more fun than I do.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

39. I think I have a good sense of humor.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Never

Almost Never

Rarely

Sometimes

Frequently

Almost Always

Always

40. I feel very self-conscious when I am with strangers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

41. I am afraid I will appear foolish to others.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

42. I think my friends find me interesting.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

43. I binge eat.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

44. If so, I feel guilty after binge eating.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

45. I engage in purging (throwing up) after meals to help with weight

management.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Please respond to numbers 46- 51 based on the following scale:

1 - Strongly Disagree

2 - Disagree

3 - Slightly Disagree

4 - Neither Agree nor Disagree

5 - Slightly Agree

6 - Agree

7 - Strongly Agree

(Please circle only one.)

46. I think I may have a problem with binge eating.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

47. I think I used to have a problem

with binge eating.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

48. I think I may have a problem with anorexia nervosa.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

49. I think I used to have a problem with anorexia nervosa.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

50. I think I may have a problem with bulimia nervosa.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

51. I think I used to have a problem with bulimia nervosa.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Please circle one.

52. I have/had friends with bulimia nervosa.

YES

NO

53. I have/had friends with anorexia nervosa.

YES

NO

THANK YOU FOR COMPLETING THIS SURVEY.

Survey questions adapted from the Index of Self-Esteem (ISE)